Mervyn peake has been one of my favourites for a very, very long time. I think I was probably in my middle teens when I first read Gormenghast; having been brought up on a steady diet of fairly po-faced sub-Tolkien fantasy, Peake’s writing hit me like the Cure’s tour bus. It was probably my first encounter with something so genuinely peculiar and strange; an exhilarating and flamboyant sort of weirdness, which offered a relief from the mundane existential trauma of growing up.

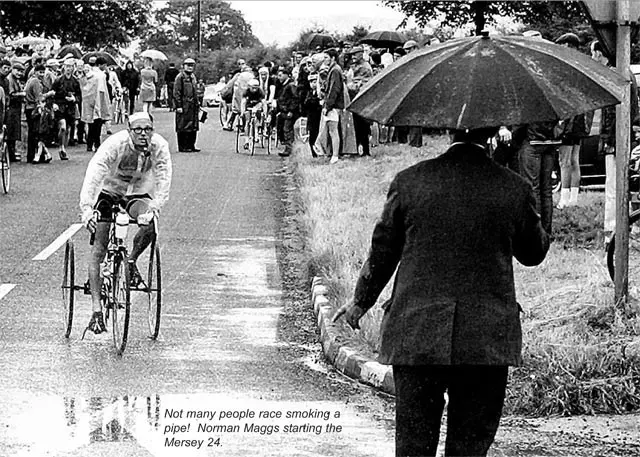

I recently discovered that my namesake Norman Maggs, a self-taught scholar who was a regular at the British Museum reading room (a self-diagnosed ‘British Museum creeper’), nicknamed his Ealing home Normanghast. Even better, it turns out that another contemporaneous Norman Maggs was a leading light of the British tricycle racing scene. Here he is, smoking a pipe at the beginning of the Mersey 24 hour time trial. Life goals.

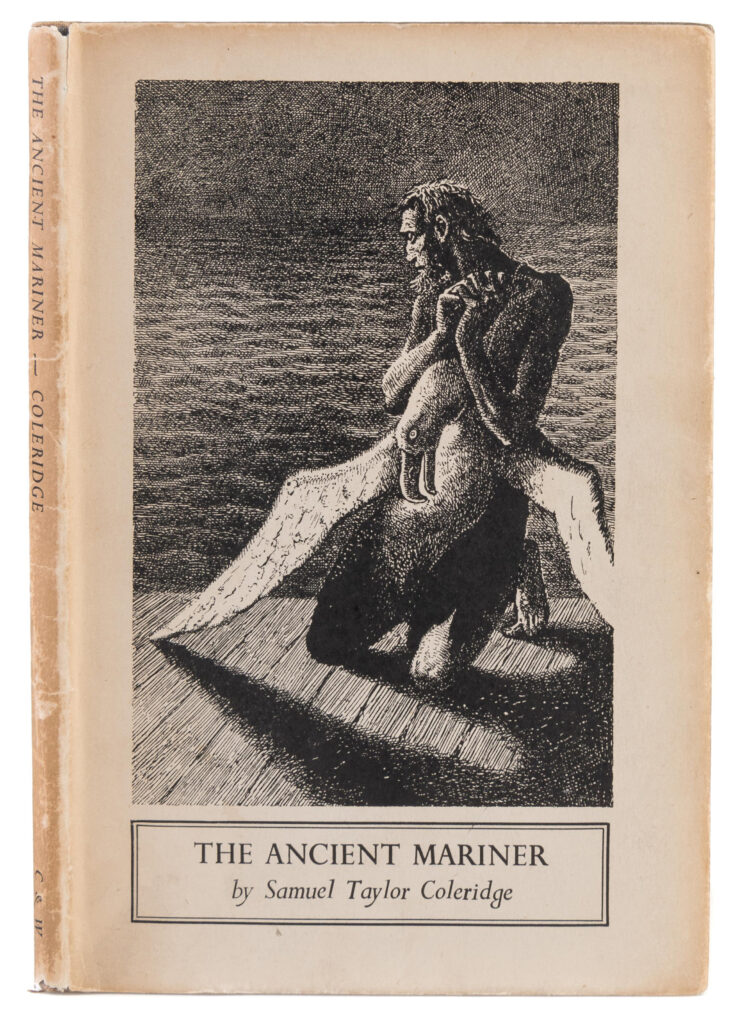

The first edition of Peake’s illustrations to Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner is surprisingly rare, and I have only handled a single copy. Published in 1943, this is one of those books which attracts spurious anecdotes about warehouses full of stock being bombed (Rex Warner’s The Aerodrome is another, although there the story does seem particularly appropriate), but it wouldn’t be a great surprise if the print run was truly limited by constraints on paper and labour.

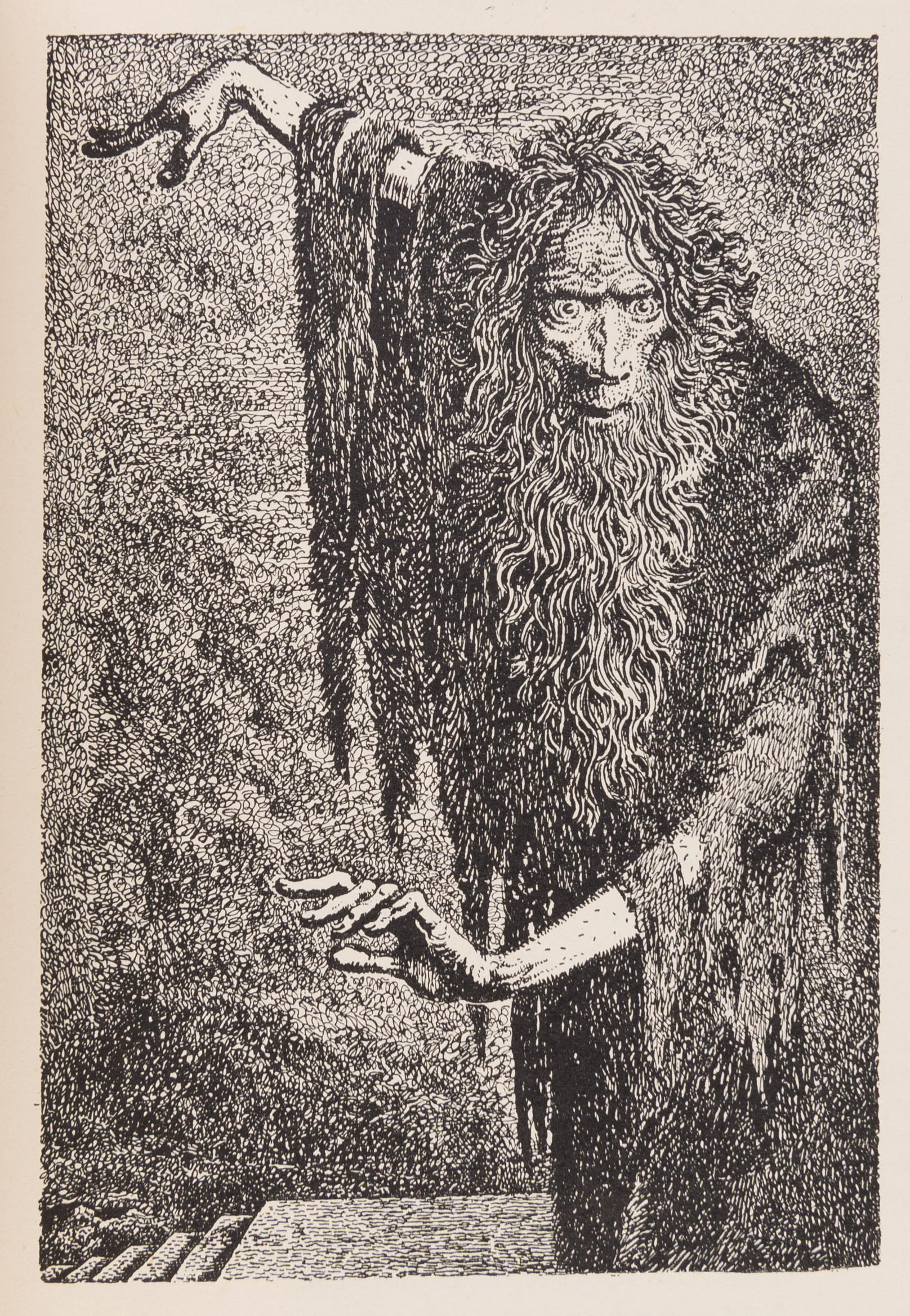

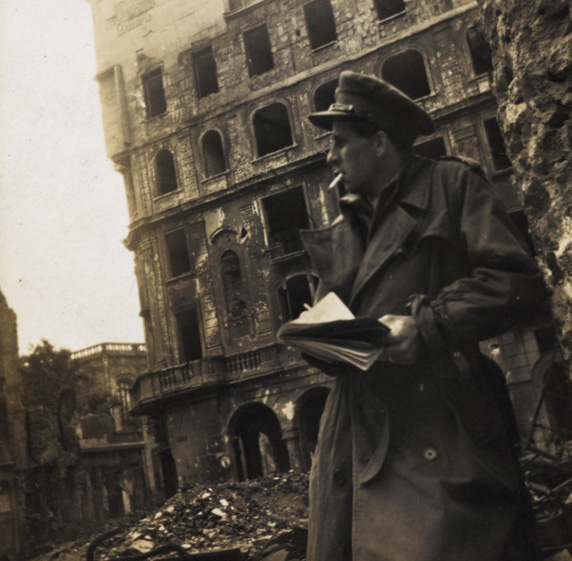

This was the first book that Peake illustrated following his demobilisation from the army after suffering from a nervous breakdown, and despite having previously published Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor, he considered that ‘all my life I have been painting and making drawings but I only started illustrating books when I was conscripted.’ Peake’s images offer up a world of stark desolation, the emaciated sailors so horrifyingly real that it seems impossible that they were not drawn directly from life, while the Mariner himself channels the mad intensity of Goya. Peake’s son, Sebastian, has explained that Gormenghast, too, was inspired by his wartime experiences, and particularly by the time spent working as a war artist at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp; “I believe now that the Holocaust was my father’s ‘heart of darkness’”.

The human suffering he witnessed was mirrored by the destruction of German cities, and in the contrast between the suffering of the body and the suffering of stone expressed in letters sent home, one can see the character of the living-city of Gormenghast begin to take shape.

“Bonn was nothing to Cologne from the point of view of destruction. It is incredible how the cathedral has remained, lifting itself high into the air so gloriously, while around it the city lies broken to pieces, and in the city I smelt for the first time in my life the sweet, pungent, musty smell of death. It is still in the air, thick, sweet, rotten and penetrating… But the cathedral arises like a dream – something quite new to me as an experience – a tall poem of stone with sudden, inspired flair of the lyric and yet with the staying power, mammoth qualities and abundance of the epic. Before it and beside me stood a German soldier, still in his war-worn, greeny-coloured uniform. His face betrayed nothing. Cologne lay about him like a shattered life – a memory torn out.” Peake in a letter to his wife, Maeve Gilmore

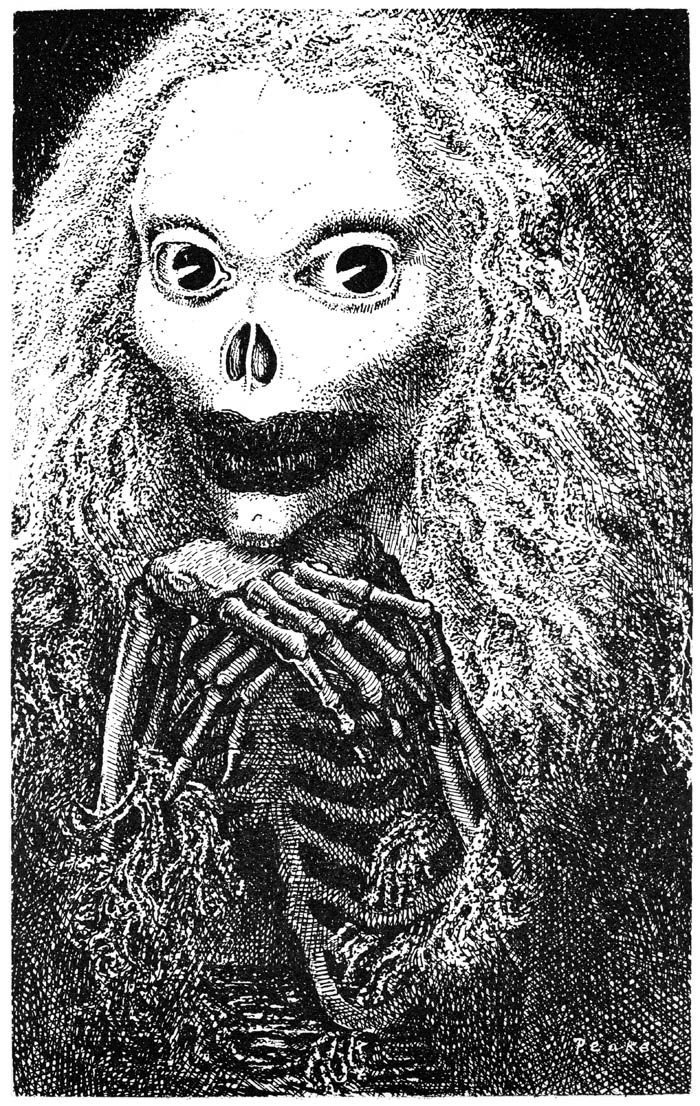

One of his illustrations, ‘Life-in-Death,’ was indeed so upsetting that it was rejected by Chatto & Windus; ‘the publishers thought that it would be unfair to the general public to have them buy the book and then come across a picture like that when turning the pages. It had to come out.’ It certainly is a distressing image and was kept out of reprints as late as 1978; the design was even shamelessly plagiarised for the dust wrapper of the first English edition of The Hounds of Tindalos, a tale of beasts so foul that ‘no words in our language can describe them!’

When seen in relation to Peake’s military service, the choice of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner seems particularly apt; Peake was himself a voyager ‘constantly on the move from unit to unit – and from regiment to regiment … this constant moving about gave me little scope for painting.’ Coleridge was one of his favourite writers, and even when suffering from advanced Parkinson’s in later life, his wife would read the poem aloud to him.

‘above all things there must be the power to slide into another man’s soul.’